Do you use web apps often? Do you want to access these apps the same way you would access a normal Mac app in your dock? Well, you can. I create dock icons for Web Apps using a few simple steps on Mac OS X.

Creating Dock Icons for Web Apps is Easy with Fluid

|

| I sometimes want to use Web Apps just like any other App on my Mac. |

- Download and launch Fluid, free software that creates a “site specific browser” for Web Apps you use all the time.

- Download an icon or .png file for the Web App you want to install. Using a web browser and search engine simply search for “Facebook icon” or “Google Docs icon” to find .icns files or .png files. Download the file you want to use to your computer. There are tons of styles available and most are for free. *For Mac users, .ico files will not work.*

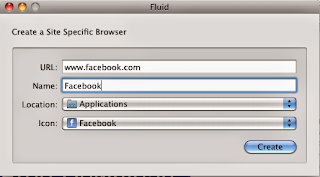

- Launch Fluid. Type the URL of your web app. I want to install Facebook so I insert “www.facebook.com” and give it a name, “Facebook." Select “Application Folder” for the location of the app.

- Upload your icon or PNG file. Select other from the menu. Choose your icon or PNG file you downloaded in step 2. You can use the “select website favicon option” but I prefer to upload my own.

- Fluid places your Web App in your Applications folder. When you launch the application it starts up and appears in the Dock just like any other application.

- Simply use the Web App like any other app. Click it in the dock and it launches as a stand-alone application.

Cool Features: You can work in your Web App environment in full-screen mode. It allows you to focus on a project without the distraction of your web browser. Gives your Web Apps like Google Calendar, Google Docs, Facebook, etc., pride of place on your dock with your other Apps.

Be aware: Only use for apps you use often to increase your productivity. Also, it can be a pain finding a decent resolution on .icns and .png files. Choose your files with care.

Be aware: Only use for apps you use often to increase your productivity. Also, it can be a pain finding a decent resolution on .icns and .png files. Choose your files with care.

.jpg/800px-Oedipus_und_die_Sphinx_(Gustave_Moreau).jpg)