Dive into our insightful analysis of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream as we explore power dynamics, Shakespeare's orientalistic imagery, and a nuanced interpretation of a specific scene involving Titania and Oberon. Our post, perfect for educators and students alike, brings a fresh perspective on this classic play.

I’ve taught high school students A Midsummer Night’s Dream several times. It’s a popular text in American schools. In fact, I even read it in high school, and I have seen it performed on stage multiple times. It’s a fun play that has worn well over the last five hundred years.

Power Plays in the Play

When teaching the play, I recommend skipping the part in the first scene where Hippolyta and Theseus talk about their wedding (and returning to it later). I go straight to the moment when Egeus comes to the court to ask Theseus to force his daughter Hermia to marry a boy she doesn’t want to marry.

I ask students to keep track of disagreements in the play. Who is arguing with whom, and what is the power differential at work? In this case, it’s a debate between an adolescent girl and her upper-class, middle-aged father, who wants to make decisions about the future of his family line. Having students identify these power struggles is an effective way to hook them onto the play. Who doesn’t enjoy a rollicking tale of parental control and teen rebellion?

If you don’t know the plot, it involves two young pairs of lovers from Athens’ aristocratic class who flee into the woods to evade parental authority and the law. I’m leaving out a few plot details, but essentially, a fairy named Puck plays with the concept of love at first sight, and chaos ensues in the forest. Even the queen and king of the fairies join the madness.

There’s a lot to say about this play—indeed, I’ve written about it previously—but in this post, I want to focus on a particular scene one may overlook when reading the play.

A Closer Look at a Particular Scene (Act 2, Scene 1)

Titania, the Queen of the fairies, has "stolen" a lovely boy from an Indian king, and her husband, Oberon, wants the boy for himself. Now, by Indian, Shakespeare means the Asian sub-continent, not the first nations inhabitants of the New World. In Shakespeare's time, Britain had already made in-roads into India and had begun what would become a long colonial presence there. There is debate among scholars as to the exact implications of this term in the play. In the late 16th century, when Shakespeare was writing, England was just beginning its interactions with India. Shakespeare wrote A Midsummer Night’s Dream: Generally in the mid-1590s (often dated around 1595–1596). The British East India Company, which began formalizing British presence in India, was established in 1600, a few years after "A Midsummer Night's Dream" was written. Indeed by Shakespeare’s time, England’s dealings with India were indeed in nascent stages. This means that while there were some interactions and awareness of India, the full-scale colonial presence hadn't been fully established yet in Shakespeare's time.

But the germ of colonial enterprise is there, in the text. Shakespeare romanticizes India.

The argument between Titania and Oberon over the "changeling boy" primarily takes place in Act 2, Scene 1. In this scene, Oberon confronts Titania about the Indian boy whom she has brought from India and is caring for. Oberon wants the boy to become one of his followers, but Titania refuses to give him up, which causes a conflict between the two characters. The scene contains key dialogues that reveal the depth of their disagreement over the boy.

When Titania explains how the boy was not stolen, but rather, she became the child's protector, Shakespeare infuses the language with orientalistic flourishes. The term "orientalism," coined by historian and post-colonial theorist Edward Said, refers to the way Western societies view Asia through a skewed and privileged lens, often exaggerating stereotypes and presenting "the Orient" as an exotic "other." While the concept of exoticization predates Said, Shakespeare’s references to India fit an early form of this tendency. For example, in describing Titania's visit, Shakespeare describes the Indian air as spiced, and he notes that Titania takes a seat on "Neptune's yellow sands". I am not sure why he refers to Neptune here, but it is a reference to the god of the sea (in Greek, Poseidon). My guess is that it is a soft allusion to the trade relations between India and Europe, a relationship that was born on the sea, but also traversed through trade routes (hence the "spiced Indian air" that also seems to allude to the export of spices from Asia).

Oberon: "I do but beg a little changeling boy to be my henchman"

While Oberon contends that Titania is a thief, the Fairy Queen explains that she came in possession of the boy because "His mother was a votaress of my order." When the mother dies in childbirth, Titania takes it upon herself to raise the boy as her own and she steals away with him - basically stealing the child from his father.

Their conflict over the boy plays a significant role in the plot development, as it prompts Oberon to instruct his sprite, Puck, to apply the juice of a magical flower to Titania's eyes while she sleeps. This leads to Titania falling in love with Bottom (who has been given a donkey's head) when she wakes up. When Titania returns to the forest with the "changeling," as she calls the boy, Oberon becomes furious when she won't share what she stole. The two royal fariy monarchs duke it out and to make a long story short, they kiss and make up — but not after Titania has her way with Bottom, and falls in love with the donkey-man.

|

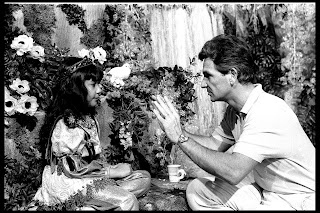

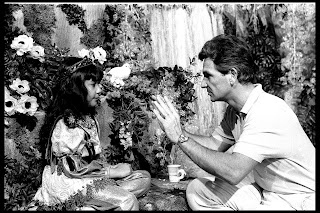

New York City Ballet production of movie version of "A Midsummer Night's Dream" with director Dan Eriksen coaching child actress playing the changeling, choreography by George Balanchine (New York). NYPL Digital Collections. |

One could interpret this episode as a metaphor for colonialism: the British Empire essentially stole territory and people, then “raised” them as its own.

Stop at the end of this scene and have your students discuss. Better yet, have them prepare discussion points based on the following prompts:

- Understanding the Conflict Between Oberon and Titania: Discuss the issue that sparks the dispute between Oberon and Titania. How does their disagreement over the “changeling boy” shape their characters and affect the overall plot?

- Traces of Early Colonial Influence in Shakespeare's Work: Examine the textual evidence that suggests the beginnings of Britain’s colonial influence on India and East Asia. How does the portrayal of the Indian boy reflect or contradict the historical context of early British-Indian relations?

- Shakespeare's Orientalism in Depicting India: Analyze how A Midsummer Night’s Dream may exemplify an “Orientalist” perspective, portraying India as mysterious, exotic, or otherworldly. Consider moments in the text where Shakespeare romanticizes India. How might this have influenced perceptions of India during his time, and how does it connect to broader discourse on Orientalism in literature?

The Changeling in Literature

|

| Cigarette Card 'The Fairies' Changeling |

Another angle is the trope of the changeling—Oberon’s label for the boy. The idea of a changeling runs throughout European folklore: a substitute child left by fairies or goblins in place of a “real” child. Even into the 19th and 20th centuries, this motif persisted, as evidenced by a set of cigarette cards referencing “The Fairies’ Changeling (Herefordshire).”

The fairies’ changeling (Herefordshire)

A mother was greatly worried about her child, for it never grew but lay in its cradle year after year. When her elder son, a soldier, returned from the wars, he refused to believe the child was his brother, declaring it was a changeling. To prove this, he blew out some eggs, filled the shells with malt and hops, and brewed them over the fire. “Though I’ve lived a thousand years,” chuckled the changeling, “this is the first time I’ve seen beer brewed in eggshells.” He then rushed from the house. Shortly afterward, a fine young man walked in—he was none other than the boy the fairies had kept for many years.

In fairy tales, the changeling can represent an unwanted child or symbolically reflect childhood fears such as “I am not wanted” or “My parents are not my real parents.” More unsettling, the trope can also point to the reality of child neglect and abuse.

Ahhh A Comedy (But, Wait. What about the Boy?)

The play is a comedy, and by the end, lovers are paired up happily, and the audience enjoys a play-within-a-play. Yet we never learn the fate of the boy. What happens to him? There’s a creative opportunity here, akin to what Jean Rhys did in Wide Sargasso Sea, to craft a story that gives voice and depth to the changeling boy from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Let’s not leave him behind; let’s give him his own narrative.

By Greig Roselli

Sources:

1. Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library. “New York City Ballet production of movie version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream with director Dan Eriksen coaching child actress playing the changeling, choreography by George Balanchine (New York).” The New York Public Library Digital Collections, 1964.

2. George Arents Collection, The New York Public Library. “The fairies’ changeling (Herefordshire).” The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

PDF Copy for Printing