Stones of Erasmus — Just plain good writing, teaching, thinking, doing, making, being, dreaming, seeing, feeling, building, creating, reading

4.4.24

Zeus Ammon at the Met: A Greek-Egyptian Syncretism in Stone

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

20.3.24

Sully Wing Secrets: Louvre's Greek and Egyptian Wonders

Discover a teacher's unique Louvre encounters, from Greek beauty to Egyptian relics. Explore beyond Mona Lisa to uncover the Louvre's heart.

|

| (2) Apollon Sauroctone |

|

| (1) Éphèbe |

![Un fleuve Barye, Antoine Louis. Un fleuve. 19th century, France. Musée du Louvre, Department of Sculptures of the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and Modern Times, inventory number RF 1560 & RF 1561. Louvre Museum, Sully, [HIST LOUVRE] Salle 134 - Salle de la maquette, Vitrine 08](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhRE9YnlXlK6KfP-A0z_dJZYnBT7_1M5T9D3tZk_gXozKs9gMd9nO9UXlkT5TkHi9T0KkSBwjL6qcfr74jTaMOtO6h47D1jJt4P6LadIo9MGzu3yL8o9KabJ2TLnGC05aMOJLGXy08A5kn4PeMuqb1xi3BchLe5z6tW_ddtYaAY0Te_gBcwPo7btQ/w180-h320/A65BC7E3-435F-4BF6-9AEE-992B60DCA921.jpg) |

| (3) Un fleuve |

![Statue of a Sphinx Musée du Louvre. Statue of a Sphinx. Circa 380-362 B.C. [?], Serapeum of Memphis, Saqqara. Musée du Louvre, Department of Egyptian Antiquities, Room 327, Sully, inventory number N 391 D. Louvre Museum](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjgUwtk13qrP7vP1aawA_H8HLkuH_Om2fdXDUYZS5rp9gzDUj93w2JqthNzZp3HNWS8AsQqXaXeJC5UwcvtUI0RDp8NLgjTSiUTlm3d7iOqPGBZHf7o5BGbsuMqcyb0dXuT7bz1agggYfGBhFF45As03mepTGdzalqV6E6H9gy3r1oIJpCqEAcp_A/w256-h320/2B604D01-4603-465D-9A7E-BE621258F15E.jpg) |

| (4) Statue of a Sphinx |

![Statue Musée du Louvre. Statue. Third Intermediate Period, circa 1069-664 B.C. [?]. Musée du Louvre, Department of Egyptian Antiquities, inventory numbers E 2410; N 1579; Clot bey C 25 no. 5. Louvre Museum](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjgbctrJI65LJI1iyrVOfQhyphenhyphene1Tc7QGTT4wcBmC08D_-9ItrigFHgGkqlDv2rPXfIA1CmP6V8ZIqsfUQ7CGr0K2fEwD4wjU7gBYdxKLbgTQEFFjb50Ge3hY9aGWehNd6EDdhxp35uN-0HYHIBL-vXWIXJD-NcecFiFCi6zVnQWKKJnMVmExZpZKfQ/w256-h320/75DFE6FB-8092-4AAD-8E84-5475A684CEDD.jpg) |

| (5) Statue |

![Jupiter Musée du Louvre. Jupiter. 2nd century A.D. [?], Italy. Musée du Louvre, Department of Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Antiquities, Room 344.](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh9FIeOZBWXHqm5AryH2Cb0EdwkG_C2QX7rHPa3IQTeF_q7JBsmrEfeSbekVmJaSLsg_k0Zb9dCdUctsB_i8rQA2dVqXkSQoBwP9IxfPLOA-5B4ufz0bVSvIVbKjqkpQeJ2U2Gl6C53r3ylcqsay29L5YfAPJNU4zaHvj3boIWM6pv3BF-rpLhZqA/w256-h320/72D6CC7E-0683-4B1E-AA7E-FA3A9611BA85.jpg) |

| (6) Jupiter |

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

1.3.24

Explore Greek & Roman Gods: Ares vs Mars - Mythology, Love, and War Insights

Dive into the fascinating world of Greek and Roman mythology with a detailed comparison between Ares and Mars. Discover their myths, lovers, and roles in ancient tales.

Hey, y’all. I’m in the Louvre Museum. Here stands Mars (or Ares to the Greeks), the deity of war, embodying cries, battles, bloodshed, and military conquest. It feels like the Romans admired him significantly, and although the Greeks certainly gave him a place of honor on Olympus, he wasn’t as much worshipped in temples as he was respected and feared. His lover was famously Aphrodite — the goddess of love. Also, in the spirit of exploring the less discussed side of history, we get to see his representation from behind. Additionally, if you’ve ever seen Ridley Scott’s ‘Prometheus’ — the prequel to the Alien movies — does the god’s face remind you of the giant humanoids from the film? And, if you’re a Percy Jackson fan, Ares plays a supporting role in the plot of the first book.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

25.12.23

The Miraculous Tale of Saint Nicholas and the Resurrected Children: A Christmas Legend

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

27.7.23

Aesthetic Thursday: Encountering St. Firmin, the Ultimate Multitasker from the 4th Century, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

| Saint Firmin |

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

24.7.23

Clip Art: Three Grecian Heads

.png) |

| "Three Grecian Heads" |

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

18.7.23

Admiring Saint Catherine of Alexandria: A 16th Century Italian Sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

16.7.23

A Marvel in Marble: The Angel Relief Sculpture by Antonio Rizzo at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

| Angel Holding a Shield, Antonio Rizzo, Italian, 1470 |

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

15.7.23

Unearthing Mysteries: An Encounter with Fortuna at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

| Fortuna (Tyche), Late Roman or Byzantine ca. 300-500 C.E. |

Upon closer inspection, you begin to notice the details etched into this statuette that elevate it from a simple representation of a goddess to a profound symbol of historical narrative. A distinguishing feature of Fortuna is her sculptural headdress, ingeniously designed to mimic a city-like fortress, replete with a gate, and walls to fortify it. The statuette portrays her with this sculptural motif of a city perched atop her head — a poignant indication of the goddess's authority and influence.

But, the statuette holds more in its petite form. Cradled in Fortuna's hand is a cornucopia - a classic emblem of abundance and prosperity. This combination, a city upon her head and a symbol of prosperity in her hand, is powerful. It's a juxtaposition that beautifully ties together the themes of urban society and fortune.

The statuette isn't merely an exquisite work of art; it's a vessel, carrying layers of symbolism and a profound narrative within it. Fortuna, adorned in her cityscape headdress, seated on a throne, paints a picture of the intricate relationship between chance or fortune and the development of civilization. It's a compelling reminder of how the evolution of societies has always been tied to the capricious hands of fate.

So, it isn't just a 'cool little statuette' - it's a piece of history, a symbol of societal evolution, and a testament to the intricate craftsmanship of the Byzantine era. It's the embodiment of the idea that every artifact carries a tale, waiting to be discovered, waiting to be told. Take a moment to admire this extraordinary piece of history and let Fortuna's tale unfold.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

14.7.23

A Glimpse of Mythology Above Grand Central Station: The Watchful Hermes

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

12.7.23

Resurrecting Adam: Tullio Lombardo's Masterpiece Restored

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

Marveling at Tullio Lombardo's Young Warrior: A Journey into Late 15th Century Venetian Art

Tucked into a portion of the east side of Central Park in New York City, nestled among a myriad of remarkable artifacts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, stands a profound example of late 15th-century Venetian art. This remarkable piece is a marble sculpture of a young warrior by Tullio Lombardo, a master of the Italian Renaissance from Venice. The immersive experience of admiring this piece face-to-face truly transcends the ordinary museum visit.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

10.7.23

Exploring Ancient Rome: The Majestic Bust of Marcus Aurelius at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

7.7.23

Exploring Artistic Marvels: Unveiling the Spinario at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

22.4.23

Clip Art: A Boy Akimbo Pondering Dasein

Source: Created by Stones of Erasmus, claymation (with digital elements added by open-source artificial intelligence). This image is created and made with love by Stones of Erasmus (stonesoferasmus.com).

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

27.3.23

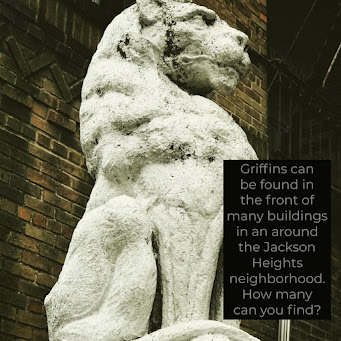

Griffins & Mythological Creatures: Architectural Motifs in the Jackson Heights Neighborhood of Queens

|

| While some of the statues in Jackson Heights may resemble guarding lions more than take-flight griffins, there is undoubtedly a family resemblance. However, I must confess that I am not a pedant when it comes to classifying mythological creatures, and their presence in the neighborhood adds to their unique character and charm. |

- 72nd Street and 35th Avenue - Griffin

- 75th Street and 35th Avenue - Griffin

- 81st Street and 37th Avenue - Griffin

- 81st Street between Northern Boulevard and 34th Avenue

- 34-48 81st Street (between 35th and 34th Avenues) - Stone carving of two Griffins above the doorway

- 80th Street between 37th and 35th Avenue

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

Clip Art: School-Aged Girl with Glasses and Braces

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

17.3.23

Clip Art: Surprised Teen Boy Close-Up

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

15.3.23

Clip Art: Endymion Sleeping on Mount Latmos

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

14.3.23

Clip Art: A Winged Griffin About to Take Flight

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

.png)