|

When I was a Roman Catholic Seminarian,

and the very young age of nineteen,

I was in a private audience with the then Pontiff

of the Roman Catholic Church, John Paul II

|

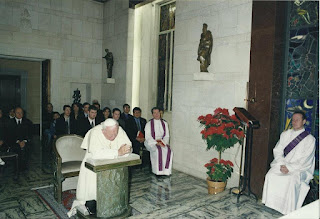

To say that I met and chatted with the leader of the Roman Catholic Church would be a stretch. But I did kiss his ring. And I got to see him in his private chapel and in his private library in the Vatican.

I attended a private audience with about twenty-five other people — mostly priests and seminarians. It was the year 2000—around Christmas time—and I was in Rome with other American seminarians from the American College in Leuven, Belgium (where I was a college seminarian at the Catholic University of Leuven). At the time I was studying to be a priest, and our group was invited to have a private audience. The story went that when John Paul II was a seminarian in Krakow, Poland, his seminary was suppressed by the Nazis and apparently, the American College, in Leuven, had sent over, secretly, supplies, books, and the sort, to Poland, as a sign of support and solidarity.

We were in Rome for two weeks, staying as guests at the Pontifical North American College (located on the Janiculum hill) — but we didn't know what day our audience would happen. There are security protocols one follows when scheduled to meet the Pope. The Vatican gave a call to our group leader, a Benedictine priest named Aurelius Boberek, the night before and he then contacted us to be on the ready. We're meeting the pope!

|

|

The Bronze Doors

|

The night I heard the message I had to scrap my plans for the following day. I was planning to visit the catacombs of Saint Callistus. Oh well, I thought, a papal visit trumps all of that. So we had to wake up early — to arrive at the Bronze doors of the Vatican Apostolic Palace at the crack of dawn. You enter the doors from the right colonnade in Saint Peter's Square. Once we were green-lit to proceed, we were inside the Apostolic Palace — which extends as a grand loggia, designed by the Renaissance artist Raphael. It serves as an official portal and links up with the jumble of buildings that comprise the palace.

John Paul II had a private chapel in the papal apartments, located in the upper floors of what is officially called the Palace of Sixtus V, where he celebrated an early mass. It was so quiet when we arrived one could hear a pin drop. The Pope enters the sanctuary fully vested and he celebrated the Mass in the old Latin rite style — facing the altar (and not facing the people). I think I read one of the readings for the Mass (Or, maybe I read the intercessions. I cannot remember, exactly). So did my classmate Brent Necaise, who was a student with me — I was from Louisiana and he was from Mississippi). Afterward, the Pope's private secretary, a fellow by the name of Stanislaus Dziwisz, escorted us to the private study (or was it the library?) of the Pope.

It was Christmas time, so in the Pope's library there was a stately Christmas tree with ornaments painted with images of John Paul II. I remember thinking that was funny for some reason. I guess if you are Pope you get used to seeing your image affixed to everything from postage stamps, money, and ornaments. I remember all of the furniture was elegant but not overstated. It was a brightly lit room. And there was a wooden barrister bookcase with nicely appointed leather-bound books.

The Pope entered shortly after we had congregated and took a seat in a white plush chair. Everyone in our group lined up to meet him one by one, by kissing his ring, and stating our home state in the United States. When it was my turn he said softly, "Oh. The Mardi Gras," because it was announced I was a seminarian from Louisiana, and when another seminarian said he was from Kentucky he said, "Oh. Race horses." And it went like that — and each of us received a rosary and a holy card.