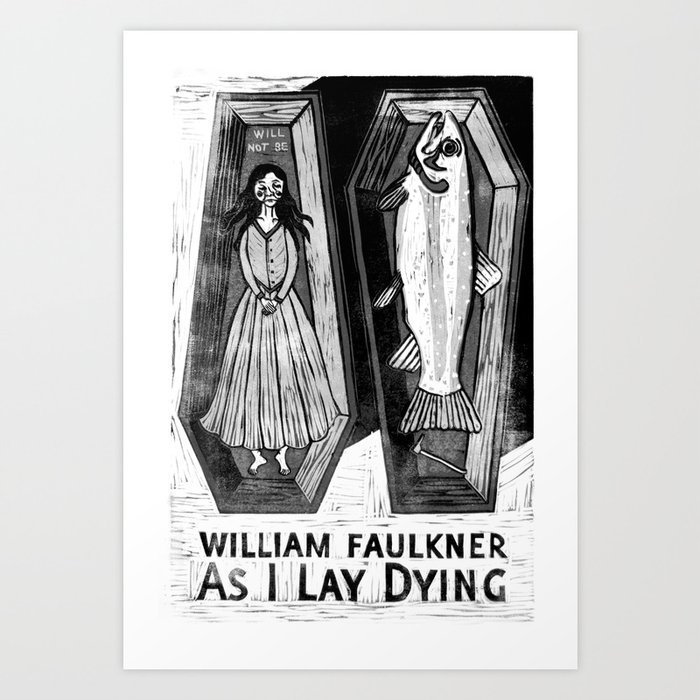

William Faulkner’s novel, As I Lay Dying, is the archetypal quest story, one of the most satisfying and basic plots in the literary canon.

William Faulkner’s novel, As I Lay Dying, is the archetypal quest story, one of the most satisfying and basic plots in the literary canon.William Faulkner’s novel, As I Lay Dying, is the archetypical quest story, one of the most satisfying and basic plots in the literary canon. Like Homer’s The Odyssey

The River as Metaphor for Story

In this post, I will explore how the madcap journey the Bundren family undertakes becomes, like an ever-changing river, a locus of pleasure in the narrative itself. I will show this using the tableau image of Darl drinking the water-filled gourd because the language and tone of this scene is inebriated with warmish cool water riddled with stars, as Darl describes it himself (8). I will then show how the narrative of the water-filled gourd is depicted as sensuous pleasure, the pleasure of the body and the readerly satisfaction of a wavelike release - in the story's end.

The Bundren Family and Their Motives

Oddly enough, the disturbing nature of the story is what makes the novel pleasurable. The motives of every Bundren family member cannot be said to be of the highest moral value. Each and every one of the clan has their own motive: Anse, the father, Cash, the eldest, Jewel, Darl, Vardaman, the youngest, and even Addie, the dead mother, all have strange desires and motives. The fact that Cash, in the novel’s opening scene constructs his mother’s coffin, as she lays dying, in a place where she can obviously see and hear him, is sadistic and disturbing. Who would do this to their own mother? After her husband has gone to work and the last “dirty snuffling nose” had gone to school, what kind of mother would go to a quiet place so she “could be quiet and hate them?” (114). But this is the kind of pleasure that Faulkner is gesturing at in this novel. Cash derives pleasure from constructing the coffin, as is shown in a chapter that lists deliciously how he made the coffin on the bevel (53). His reason? “The animal magnetism of a dead body makes the stress come slanting, so the seams and joints of a coffin are made on a bevel” (53).This pleasure is what makes one reader say, “this book is so funny” and another reader to say, “this book is so sick!” There is a voyeurism ingrained in the reader to want to find out more about this strange, poor family and what compels them to undertake their journey no matter how much you feel or think their journey is depraved. The reader is interested in as many details as can be garnered that can aid in putting the narrative pieces together to understand the journey arc of the novel. This is highly pleasurable. Added to this is the structure of the novel itself. It is told by a series of monologues written in a stream of consciousness style. The reader puts together the pieces of the Bundren’s journey through the varied and limited mental states of the characters. Being inside of the mind of a character provides pleasure, for it is a romp within the mental imagery of another “person”.

Darl as the Central Character

The character of Darl comprises many of the scenes in the book. We are inside Darl’s mind, it seems, more than any other character. Darl seems to be a logical character, but one notices that he takes too many “soft right angles.” There is something sinister in his immediacy with the world around him. Darl emphasizes an unmediated relationship to the world. His conception of the world is dictated solely by sensuosity. Although this will prove to be his demise into insanity, he finds pleasure in what he apprehends to be intuitively sensuous and tangible. He is not interested as much in the concern and care for other human beings as long as they fit into his own sensuous relationship to reality. For example, the scene with the water-filled gourd warrants how Darl’s sensuous response to things around him becomes a fixated locus of pleasure in the narrative arc of the story’s journey.

The Water-Filled Gourd

Around the side of the house, the Bundrens have set a cedar bucket to allow water to sit. It gives the water a sweet taste. As the father Anse points out, water tastes sweetest when it has sat in a cedar bucket for at least six hours, not in metal. It’s “warmish-cool, with a faint taste like the hot July wind in cedar trees smells" (8). Once the water has sat for a time, it is poured into a gourd. What enhances the pleasure for the reader in this scene is how Faulkner situates the text within the narrative structure of the chapter. We are inside Darl’s troubled head here. But we hear his father ask him, “Where’s Jewel?” (8). It is in the interstices of this question that Darl fantasizes about going to the water-filled gourd at night, stirred awake, to see the stars in the water inside the gourd, to be intoxicated into an erotic reverie. But the text reverts back to reality. Back to the scene where his father had asked him about Jewel’s whereabouts. The text brings us in and out of internal journeys into external journeys and out again and back again. This is what gives the novel a heightened sense of journey for the reader. The pleasure of the text is not only Darl’s own bodily pleasure, but the text itself becomes an erogenous zone. The text is a sensuous locus of pleasure as well as the pleasure of the character Darl himself, despite Darl’s own descent into madness.

When Darl secretly drinks from the water-filled gourd there is an immediate sense of sensuous pleasure for him as it is for anyone who would drink this sweet tasting water. But for Darl, the pleasure goes deeper than just the sweet taste of drinking from the still gourd. For Darl, the pleasure goes deeper. More insane. It becomes erotic. But erotic to the extent of making the ritual act a fetish. The pleasure of the water-filled gourd for Darl comes from the ritual of drinking from it at night, when no one is looking; it becomes a private act. For Darl, the sensuousness of rain and water is a private world of his own is pleasure. Home for Darl is the comfort of his own mind and body. So when he is in a strange place he thinks, “How often have I lain beneath rain on a strange roof, thinking of home” (52).

What is a simple pleasure of drinking for Anse, for Darl, on the other hand, takes on nuances of pleasure as he makes a ritual of the journey to the water-filled gourd at night. He makes sure everyone in the house is sleeping before he commences to partake of the gourd. It becomes a journey of pure sensual pleasure for Darl. There is at once the pleasure, the bodily and erotic pleasure that Darl receives from his ritual and the voyeurism of the reader as he reads the narrative story as it unfolds. The effect of the stream of consciousness narration allows the reader to sense the language that Darl uses in describing the water-filled gourd. It is almost as if he is describing a sexual encounter with another person. Not a water-filled gourd. The tone of the passage shifts from Darl saying that he has dipped the gourd into the cedar bucket to drink, as a mere empirical observation, into an almost mystic reverie of the act of drinking from the gourd.

Darl describes the water as black, like the night, “the still surface of the water a round orifice in nothingness” (8). For Darl, the opening of the gourd and the still, black water, becomes an image of a round orifice in nothingness. The use of the word “orifice” is telling here because the word has a bodily connotation. Of all the words Darl could conjure for “opening,” he uses orifice, as in the bodily opening of the nose or mouth. “Orifice,” because it comes from the Latin word “to make a mouth” is evocative of a mouth opening, or yawning. For Darl, this yawn is an entrance into nothingness. Faulkner does not ignore the pleasures of the body. This is the developing sexuality of an adolescent who knows he is growing bigger and older (8). The language Darl uses of water, of openings, and of nothingness lends itself to a language of sexuality. He is using language to describe sexual pleasure, the pleasure of the body’s journey into nothingness, into a kind of orgasm.

The fantasy continues as Darl describes the feel of the wind on his own body, lying with his shirttail up, “feeling myself without touching myself, feeling the cool silence blowing upon my parts” (8). Darl is exposing his body to the open air to feel his own body without feeling, or touching his own body. It is the pleasure of the text that Roland Barthes speaks about when he describes reading a text like seeing a gap of flesh between a person’s shirt and pants, the layer of flesh that peeks out from between that flashes in the mind’s eye. Reading becomes a pleasure like the pleasure of seeing a flash of bodily flesh between clothes, a horizon of pleasure readable and at the same time physical. The pleasure of the text here is in degrees and perhaps different every time we go back to the passage, as we zoom in and out, noticing details on second, third, fourth, fifth, or even after ten times of reading the same passage. We miss things because we read in waves. We don’t take it all in at a first glance. In this scene, Darl and the water-filled gourd, there is a gradual ascent in the intensity of pleasure in Darl’s experience of the drinking the warmish cool water. And as it is a gradual experience of sensuosity for Darl, so it is for the reader. So what happens, is that the reader and the text have a kind of dance with the narrative. Like a wave coming to the shore, there is a crescendo of understanding and pleasure that releases in the end. This is where the satisfaction is, in the release. Only to begin again with a different wave that rises to a qualitatively different degree of satisfaction. This reading in waves accounts for the varying kinds of pleasure readers derive from reading the same text.

The pleasure of the body is a pleasure that is at once cerebral and physical. Darl simultaneously wants the sensuousness of his own body to be felt, but also the cerebral nature of mind to feel without touching. This is difficult to capture in language. But Faulkner seems to be able to stretch language to embody not only the mind but to bring out the carnal as well. In this scene, there is the sensuous drinking of the black, sweet water at night when no one is looking. Then there is the lifting of his shirttail in the night to expose his skin to the cool night air so he can feel without touching his own body. The narrative has gone into the erotic territory of the body within the text.

A Series of Crescendos and Releases

And this is how the novel becomes pleasurable and satisfying. It is a series of crescendos and releases. As the Bundrens move Addie’s body, the pleasure of the text is the flow of the narrative journey. Darl’s journey is an ebb flow into insanity. The deeper he goes into the pleasures of the immediate nothingness, the more the language becomes non-symbolic. Darl’s language breaks down. By the novel’s end he is only able to utter, “Yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes” (173). Darl, as prefaced by his ritual with the water-filled gourd as entered completely into a search for pleasure that he has lost connection with a meaning structure. By the time the coffin with Addie’s body finally crosses the river and makes it to Jefferson, Darl has been lost “in the quiet interstices” (173). Anse gets a new Bundren. Addie rests in peace. Vardaman gets his red train. Dewey Dell. Jewel. All the rest have reached release. For now. Until the next inevitable crescendo begins.

Works Cited:

Barthes, Roland. The Pleasure of the Text .

.

Faulkner, William. As I Lay Dying . The Library of America, 1930, 1957.

. The Library of America, 1930, 1957.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Be courteous. Speak your mind. Don’t be rude. Share.